8-bit VAE: A latent variable model for NES music

in Blog / Misc

In this post, I want to show you all 8-bit VAE, a latent variable model for Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) music. Before diving into the details, here are a couple of samples derived from the model:

In the rest of this post, I want to discuss some aspects of the training set, the data representation, and finally the model itself.

The NES Database

Our goal is to generate music similar to the songs that appear in NES games, both in style and instruments. In order to do so, we require an original set of NES music and a way of reproducing the sounds generated from an NES synthesizer. High-quality NES music is available online from places such as VGMusic.com; however, a priori there is no access to the underlying musical elements such as notes. Moreover, even if we had access to such elements, we would still need to find a way to translate those scores back into music through the synthesizer. Fortunately, both of these concerns were adressed completely with the introduction of the Nintendo Entertainment System Music Database (NES-MDB) by Donahue et. al. [2]. In their work, they prepared a python library nesmdb, which allows the user to easily interact with the NES synthesizer. Moreover, nesmdb allows the user to actually reproduce NES soundtracks with exact timing and expressive attributes. To this end, they kindly prepared over 5,000 NES tracks in a format which could be used with the library.

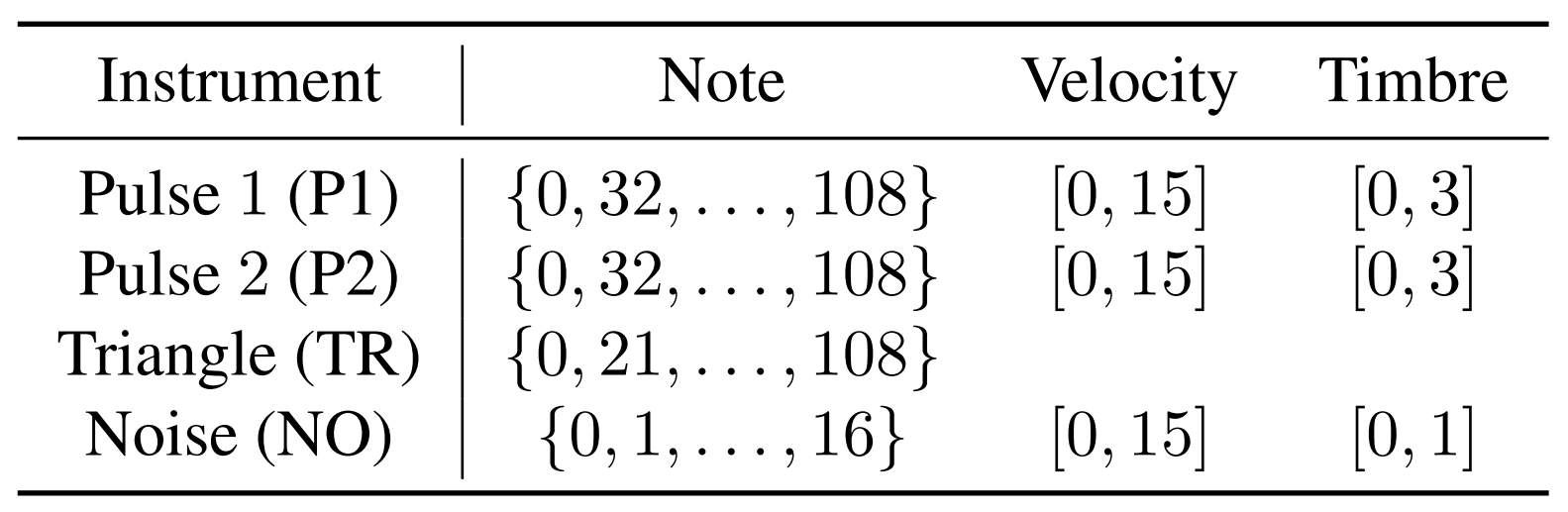

There are four instruments (referred to here as voices) that can be used with the synthesizer. These are Pulse 1 (P1), Pulse 2 (P2), Triangle (TR), and Noise (NO). Each of these instruments come with its own range of pitches, velocities, and timbre, as depicted in Figure 1. For more in-depth information about this dataset and the synthesizer, please look at their github page or their paper.

There are two fascinating aspects of this dataset. The first is that it is multi-instrumental. Most music generation models focus primarily on piano or more generally single-instrument pieces. Introducing a host of instruments complicates the dynamics, but fortunately for us, the limitations in the NES synthesizer actually provide a helpful restriction: Any voice can only hold one note at a time. In particular, this means that while we may have multiple voices holding different notes at once, they will be holding only one note each. We will explicitly use this fact later on.

The second interesting tidbit about this dataset is the inclusion of exact timings and expressive attributes arising from the velocity and timbre elements. As it turns out, the nesmdb library is more than capable of playing scores without requiring values for velocity or timbre. We will call scores coupled with their expressive attributes expressive scores, and those without we will call separated scores. Unsurprisingly, there can be a large difference between the music produced from an expressive score versus its separated variant.

For the purposes of this note, we will be focusing strictly on separated scores. For a proof of concept, such a restriction is forgivable. Moreover, given the limited computational power at my disposal, I had no other choice. Future work (and when I come in posession of more computational power) should certainly remove this restriction. For the sake of simplicity, I also removed the NO voice.

Data Representation

Originally, Donahue et. al. presented the separated scores as NumPy arrays of shape $N \times 4$, where $N$ is the number of timesteps, and 4 is the number of voices. The $ij$-th entry of the array corresponded to the pitch of the $j$th instrument at the $i$th timestep, where each timestep corresponds to $\frac{1}{24}$th of a second. Using the data in this form can cause a lot of trouble. Due to the high sampling rate, most voices’ pitch don’t change frequently as we move along time. Intuitively, one should suspect that notes are usually held for longer than $\frac{1}{24}$th of a second. In practice, this means that we can achieve artificially high accuracy in predicting the pitches for the next timestep by using the current values as the prediction. This spells out disaster if our goal is to produce sounds which are not just holding a single note for an extended period of time. To fix this issue, we modify the data structure into a sparse event representation through an iterative process. We first take the starting values of P1, P2, and TR and make a sequence of three elements of them. Then, we count for how many timesteps do we hold all three of values constant, and we make that count the 4th value. We then once again compute the current values of P1, P2, and TR then proceed as before. To distinguish between voices, we shift the P2 pitches by 77 (the number of P1 pitches), as well as the TR pitches by 144, and the count by 242. We also impose a restriction on how long we can hold notes for, and only allow the count to go up to 32. Summarizing this discussion, we have:

- 77 P1 pitch events (0 - 76)

- 77 P2 pitch events (77 - 153)

- 89 TR pitch events (174 - 242)

- 32 count events (243 - 274)

Notice that since each voice can only hold one pitch at a time, this is well-defined. For the purposes of this note, I broke up each song into sections of 52 events long.

Generative model: VAE

Modelling long-term depencies in sequential data remains a difficult problem for a lot of domains. This is especially troubling in the realm of music, where even with our special data representation, it would take roughly a thousand event-long sequence to generate a minute of music. While Google’s Magenta has achieved great success in this department with their Music Transformer found in the work of Huang et. al [1], such a model was too computationally intensive for me to use. Keeping these computational costs in mind, I looked for a model that would allow me to make pieces of music which I could string together in a natural way, hopefully achieving a semblance of long-term structure. Naturally, this led to me consider a variational autoencoder architecture, since an interpolation in the latent space would hopefully allow for longer pieces of music.

I’ll briefly discuss variational autoencoders here for the uninitiated reader, but for a less terse introduction, I would suggest to look elsewhere.

Let’s establish some notation. Let $x = (x_1, … , x_T)$ denote some sequential data, following some distribution. We make the fundamental assumption that there exists some latent variable $z \sim \mathcal{N}(0,I)$, such that the density of $x$ given $z$ \[p(x | z) = p(x_1 | z) \prod_{t=2}^T p(x_{t}| x_1, ..., x_{t-1}, z)\]

is easy to sample. We can model \[p(x_t | x_1, ... , x_{t-1}, z) := f_{\theta}(x_t,h_t,z),\]

where $f_{\theta}$ is a recurrent neural network with parameters $\theta$ and $h_t$ is the hidden state at time $t$. To endow meaning to the latent space, we’ll also make the assumption that \[z | x \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu_{\phi}(x),\sigma_{\phi}(x))\]

for some neural networks $\mu$ and $\sigma$ with parameters $\phi$. From this point of view, we can think of $\mu$ as an encoder and $f$ as a decoder. To train this model, we will do so by optimizing a lower bound on the the log-likelihood: \[\begin{aligned} \log p_{\theta}(x) &= \log \int p(x,z) dz \\ &= \log \int \frac{p(x,z)}{q(z|x)} q(z|x) dz \\ &= \log \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q} \left[ \frac{p(x,z)}{q(z|x)} \right] \\ &\geq \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{p(x,z)}{q(z|x)} \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q} [ \log p(x|z) ] - \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q} \left[ \log \frac{q(z|x)}{p(z)} \right] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{z \sim q} [\log p(x|z)] - \text{KL}( q(z | x) || p(z)) \end{aligned}\]

where the inequality follows from Jensen’s inequality and the last term is the KL divergence between $q$ and $p$. As it turns out, the KL term can be computed explicitly, hence we can use the final term on the right hand side as an objective for training. If done right, then the latent space should contain enough information so that the reconstruction error (the first term on the right) is low, but not so much so that the KL term starts to blow up. In particular, we can hope that for any $z$, sampling from the conditional distribution of $x$ given $z$ will yield a snip of music, as opposed to cacophonous sound. In practice, however, there can be a lot of complications to get this balance just right, which necessitates the use of tricks. I won’t delve into the tricks here, but one can feel to look at my github page for more details on the training.

Future Work

There are two things I believe should have the utmost priority when it comes to future work. The first and foremost is to find a way to include velocity and timbre into the computations. There are a few ways of doing this, such as by widening the vocabulary to include velocity and timbre change of events or by having a network that can learn to map separated scores to expressive scores. The former seems to be intuitive appealing, but it’s easy to see how a naive implementation would lead to very large sequences.

The second problem is involves dealing with large sequences. In theory, nothing is stopping us from using large sequences than the small length 52 sequences we are using. In practice, however, training becomes much more difficult and the complications I mentioned earlier only get worse. While the interpolation trick allows us to skirt around the issue, finding a more direct and natural way to sample music for longer than few seconds would be ideal.

Bibliography

[1] Huang, C., Vaswani, A., Uszkoreit, J., Shazeer, N., Hawthorne, C.. Dai, A., Hoffman, M., and Eck, D. An improved relative self-attention mechanism for transformer with application to music generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1809.04281, (2018).

[2] Donahue, C., Mao, H. and McAuley, J. The NES Music Database: A multi-instrumental dataset with expressive performance attributes, ISMIR (2018).